The Italian Renaissance of Swordsmanship, Wrestling, and Boxing | FIGHTLAND

This article is part of a series of the European Masters of Defence. Explorations of other countries are forthcoming.

The fall of the Roman Empire did not mean the death of martial arts in Italy. Romans were adept at blade fighting, and in fact, many of the Medieval masters utilized the Roman knife fighting traditions in their own systems. In the middle ages, every man, especially those who had obligations as part of the feudal system, would be required to be proficient at fighting, especially as means of warfare. Those skills were, at the time, taught on a local level, handed down from generation to generation and practiced as part of a community, tribe, farm, or family.

Between the 13th and 17th centuries, fighting changed drastically in Italy and the rest of Europe due to a number of factors. The expanding use of firearms in warfare negated the need for the military to rely on the more antiquated fighting styles of Medieval and ancient armies. This does not mean that battles in the Renaissance era were fought solely using guns, but rather that firearms and cannons changed the range of fighting in the 16th century. Across Europe, the demand for a scientific and scholarly approach for fighting increased, and in lieu of specific military training, expert swordsmen, referred to as Masters of Defence, provided martial arts training to gentleman and military officers. These Masters of Defence were martial arts instructors of the highest pedigree, and their fighting tactics represented a cultural shift in the countries in which they lived. In Italy, Masters of Defence wrote expansive manuals on their fighting techniques, operated fencing schools that included conditioning and sparring, and created a style that would be studied by other fighting art enthusiasts, yet reviled by Masters in other European countries, especially England.

As the dark Middle Ages came to an end and the Renaissance loomed on the cultural horizon, the study of swordsmanship became a gentlemanly pursuit, rather than a military one, and Masters of Defence taught tactics that were more likely to be used in fights between two individuals rather than in a multi-person fight on the battlefield. In the 1400s, the demand for fighting schools expanded, and Milan, Venice, Verona, and Bologna all had schools taught by Masters of Defence. Under the Masters’ tutelage, combat methodologies became more sophisticated and streamlined, due in part to technological advances in combat weaponry and armament, as well as the proliferation of firearms, and an increasingly armed and educated middle class. Using new materials and construction, swordsmiths produced weapons lighter than their Medieval predecessors, and the thus the rapier became the primary sword type to be used by the Masters of Defence. Because of its light weight and exceedingly thin body, the rapier moved sword fighting from large, broad strokes to the finer, more accurate thrusting approach. A precise hand was needed to correctly land a thrust.

Wikimedia Commons

The advances in combat technology led to a decrease in military training for broadsword and other spear or bladed weapons. Instead, swordsmanship became the pursuit of gentlemen interested in learning the scientific art of sword fighting. According to martial arts historian Thomas Green, fighting manuals produced by Masters of Defence proliferated from the 1200s to the 1600s, first by hand and later by printing press. A Master of Defence was not to be mistaken as a dilettante, or even a ‘regular’ practitioner of fighting. A Master of Defence was adept at all of the weapons of the period, including sword, staff, dagger, staff, shield, and empty-hand combat. As English Masster George Silver wrote in 1599, “A Master of Defence is he who can take to the field and know that he shall not come to any harm.”

Masters of Defence were the enlightened version of the Medieval Knight. Like his predecessor, the Master of Defence was not only skilled in the art of combat, he was also supposed to possess “reason, courage, strength, dexterity, knowledge, judgement, and experience.” As a Master was a teacher, he must also be skilled in pedagogy, able to “explain without confusion what it is that he wishes” his student do in a particular moment. And of course, a Master of Defence must always be original, never passing off for his own the technique of others.

Interestingly, the popularity of training with a Master of Defence instigated an epistemic discussion about the pedagogical resonance of learning via treatise in lieu of in-person training. In the late 16th and 17th centuries, and continuing on for many years in the future, the debate raged as to whether one could truly learn the intricacies of combatives through the written word. Ideally, of course, a student would dedicate himself to a Master of Defence, but not all those interested in fighting arts had access to such a teacher. Masters were unanimous that students should learn in person, but there remained a demand for texts that detailed specific techniques, formations, and theories, that one could study and implement in practice. This demand, coupled with the renaissance in learning that coincided with the advent of the printing press, required that Masters of Defence be able not only to teach students in person, but also to be able to clearly articulate their expertise in writing. This new requirement of martial arts instructions via belles-lettres, called la communicative, called back to the Socratic methodology. Masters of Defence would sometimes write their treatises as if they were an actual training session, providing a dialogue where the pupil would ask questions of the teacher. Nearly every Master experimented with the art of explication in their own written work, although the most effective approach seems to be the universal clarity of diagrams and drawings rather than text alone.

Wikimedia Commons

The fascination in the varied techniques of swordsmen across Europe meant that Masters of Defence would publish their combat manuals in their own language, as well as provide for the translation of their text into other languages. English practitioners were especially invested in learning the ‘foreign’ fighting methods, and so Masters from Italy, Spain, and Germany had their treatises translated, often rather poorly, into English. Although the English studied foreign fighting manuals, they did not always agree with their approaches.

Although nearly every European country had their own coterie of experts, the Italian and Spanish masters were in vogue amongst trendy and young middle and upper class men, especially in England. In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, first published in 1597, Juliet’s cousin, Tybalt, is described as adept in the new Italian style of fighting. Shakespeare picks up on this difference between the English and Italian approach, as Mercutio describes Tybalt’s fighting style to Romeo’s cousin, Benvolio:

He fights as you sing prick-song: keeps time, distance, and proportion. He rests his minim rests, one, two, and the third in your bosom. The very butcher of a silk button. A duelist, a duelist. A gentleman of the very first house, of the first and second cause. Ah, the immortal passado! the punto reverse! the hay! (Act 2, scene 4).

According to Shakespeare scholar, Neil MacGregor, Mercutio critiques Tybalt’s Italian training by quoting English Master of Defence, George Silver, who, in his treatise on swordsmanship, criticized the Italian style. To Shakespeare’s audience, Tybalt’s Italian swordsmanship reveals the Capulet’s otherness, while the Montagues, even though technically Italian characters, themselves, are aligned with the solid (if stolid) combative style of the English. The English had their own cohort of Masters of Defence, who, not terribly surprisingly, were not enthralled with the Italian combat craft. But many of the Italian Masters are remembered today as the arbiters of scholarship in the quest for fighting prowess.

Pietro Monte (sometimes spelled Monti) was a 15th century swordsman and master at arms who taught fighting arts to gentry across Italy and Spain. Monte wrote numerous texts on martial arts and general military strategy, as well as treatises on the benefits of exercise. Leonardo da Vinci, while considering the trajectory of javelins thrown from a sling, wrote a note to himself to ask “Pietro Monti” for his thoughts. In addition to being a friend of Leonardo da Vinci, Monte instructed Galeazzo da San Severino in wrestling, as remembered in Baldassare Castiglione’s Libro del Cortegiano. San Severino was member of Milan’s famous Sforza family that ruled during the Renaissance in Italy and was praised for his athleticism and skill in handling a number of weapons, all taught to him by Monte.

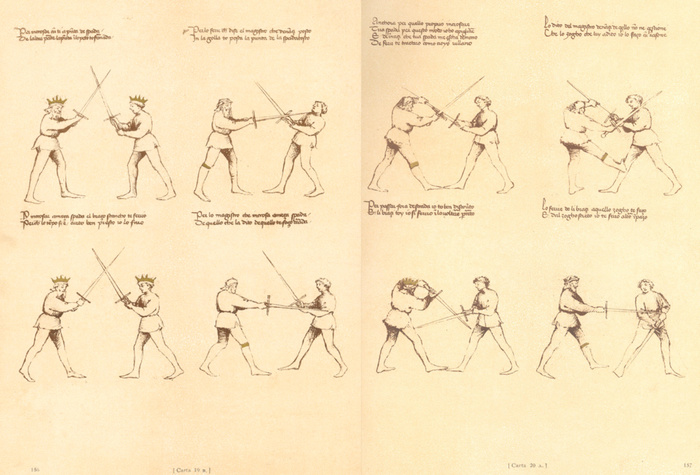

From Fiore's Flos Duellatorum (Wikimedia Commons)

Monte himself came from a long line of Italian fighting masters, many of whom were scholars outside of the fighting world. Master Filippo di Bartolomeo Dardi operated a fencing school in Bologna, Italy, where he was a professor of mathematics and astrology at Bologna University in the early 15th century. Bologna was also home to Fiore dei Liberi, master of the long-sword and author of the 1410 illustrated combat manual called Flos Duellatorum, which in Latin means “Flower of Battle.” Dardi originally studied martial arts under the German masters, but in his nearly fifty years as an experienced swordsman, he created his own approach to the long-sword which would become synonymous with the Italian school of fighting.

Fiore’s Flos duellatorum contained strategy for fighting in a number of different configurations with assorted weapons, including knife fighting, knife-versus-empty-hand strategy, spear and staff systems, two-handed sword techniques for knights, and empty-hand combat. Fiore discusses two different approaches to wrestling, that for recreation or sport, and wrestling that should be used in ‘anger,’ when one’s life was truly at stake. In the case of the latter, he instructed readers on the intricacies of locks (ligadure) to subdue an opponent or breaks (roture) to destroy an arm or leg.

Fiore’s wrestling instruction, which includes his methods for unarmed defense against an opponent with a knife, is thorough and brutal. His techniques are not just wrestling, but more of what we would refer to, in today’s vernacular, as self-defense. His treatise includes neck breaks, groin shots, and driving one’s palm into an enemy’s nose and then immediately clawing his eyes. All of his techniques also include a counter, and a counter to the counter. Flos Duellatorum was one of the only Italian text of the period to include unarmed combat techniques. The English and Germans both produced many more manuals on unarmed combat, yet it is the Italian Pietro Monte who is remembered as one of the most famous Masters of Defense of the period, and one of the few who taught a holistic approach to martial arts training.

Monte believed that wrestling was the foundation of all martial arts, and since all weapon systems that he taught included techniques to disarm an opponent, he believed that his practitioners should understand the basics of wrestling so that if they were unarmed, they could still defend themselves. Monte’s most interesting text, Exercitiorum Atque Artis Militaris Collectanea, or “Collected Martial Arts and Exercises,” also known as Collectanea, is particularly useful to fight historians because it included his writing on fitness as well as martial arts techniques. A product of his time, Monte promoted general health using the Humour theory of the Middle Ages to articulate his approach. The Four Humours were elements that made up the body—phlegmatic, choleric, melancholy, and sanguine—and dealt with different aspects of the human condition. He believed that not only should one’s humours be in balance for health, but that a skilled fighter would particularly need to be balanced in order to avoid making mistakes by being too aggressive, impetuous, or passive. Monte’s approach, which epitomized the Italian style, emphasized light footwork, requiring that fighters be lean and supple rather than large and muscular. Perhaps this is what disgusted the English Masters, that a man should be essentially small rather than brawny.

Not all Italians were built this way, nor did all Italians necessarily revel in the delicacy of rapier fighting. Emperor Maximilian I, who ruled the Holy Roman Empire 1493 to 1519, is depicted in his autobiography as participating in what appears to be a kicking contest in which his Holiness eschewed rules or decorum by stomping on his opponent’s calves, kicking them in the knee, standing on their feet, and punching one man in the face. Interestingly, the Emperor’s aggressive style was more akin to the fighting modes of the masses rather than the elite.

Wikimedia Commons

By the mid-16th century, the Italian cities of Venice and Pisa, as well as some smaller hamlets, became renowned across Europe for their violent mass fighting events, known battagliola. These ‘war games’ were designed to be both practice for battle and a cathartic experience for the lower classes to blow off steam. The first and most popular version of the Italian battagliole consisted of mass sticks fights, known as the guerre di canne, and took place between two large factions who would fight for the conquest of a bridge. According to historian Robert Charles Davis, the battagliole was, at times, an orchestrated brawl involving city magistrates and aristocrats designed to entertain visiting note worthies, including England’s King Henry VIIl, who distained the fights as not quite war, but too bloody for sport. The other, and more frequent, iteration of the battagliole was spontaneous, where men would gather at the bridge, sticks in hand, and fight, with no rules or regulations or, to some spectators, even a purpose.

The games could easily turn deadly if fighters morphed their sticks into spears, which they did by sharpening the ends and soaking them in boiling water to harden. To ward off the fatal blows, the men would don an assortment of body armor that consisted of antiquated suites of iron, handmade leather torso covers, or odd pieces of chain mail. Protected by shoddy armor, welding sticks, and fighting for what was a seemingly unknown purpose, the battagliole appears to have been truly a pastime to Medieval Italians in various cities, a social cathexis that, while popular, eventually became too violent (and perhaps pointless) for city administrators. The guerre di canne was banned by the end of the 16th century (although it still continued in underground brawls), only to be replaced with the guerre di pugni, mass boxing matches.

The guerre di pugni actually had more in common with Pietro Monte and other Italian Masters of Defence than it did with its weaponized cousin, the guerre di canne. The pugni fighters, while unarmed, were faster and more precise. In some battagliolie, pugni and canne fighters would end up facing each other, whether by design or by disarmament. The pugni were reportedly able to overcome the canne fighters most of the time because they were not encumbered with heavy weapons or body armor. The Venetian pugilists in particular were said to be skilled in throwing straight jabs and crosses, which apparently baffled fighters untrained in empty hand fighting. Swinging roundly, the untrained boxers were quickly put down by the Venetian pugni. Even soldiers who joined in the battagliole and were adroit in the handling of swords and spears, though not at empty-hand combat, were at a loss when faced with the accuracy of a well-practiced Italian boxer. The best of the guerre di pugni were, in their own way, a poor man’s version of a Master of Defence.

Fighting in Medieval and Renaissance Italy was as striated, it seems, as social class in general. The middle and upper echelons sought the chic, perhaps foppish approach to combat taught by the Masters of Defence, while the lower classes fought, pell-mell and in mass, in battagliole, with sticks and fists. Both groups were, perhaps, training for the version of fighting that they would most likely encounter in their lifetime. The middle and upper classes prepared for single-opponent combat and the exactitude required of fighting a gentleman’s duel. Working-class men, meanwhile, lived in congested areas, and were exposed to riots and brawls, as well as the likelihood, if conscripted, to serve as part of the infantry in Italy’s frequent wars. It was only in the sports of boxing and wrestling that class, strength, and size became secondary to the skill of the pugilist.

The Italian Renaissance not only brought about a rebirth of art, music, and culture, but also a renewed interest in the science of fighting. The Masters of Defence are remembered today as the scholars of the period, sharing their knowledge with students with the time and money to pay for their combat education. But even the poorer men of Italy experimented with combat methods, testing their fighting techniques in the laboratory of the street fight rather than the controlled sparring of a fencing school. And they all seemed to have come, in their own way, to the same conclusion. That skill can triumph strength and brains can beat brawn. And that boxing may be the great equalizer.

Check out these related stories:

The Fall of Rome, the End of Fighting Sports

Real Irish Fighting: A History of Shillelagh Law and Hob-Nailed Boot Stomping

Fighting the Shackles of Slavery: ‘Kicking and Knocking’ in the Antebellum South

view original article >>Comments

Search for:

- UFC News

- TUF News

- Bellator News

- WSOF News

- Invicta FC News

- ONE FC News

- Boxing News

- Kickboxing News

- Glory News

- EBI News